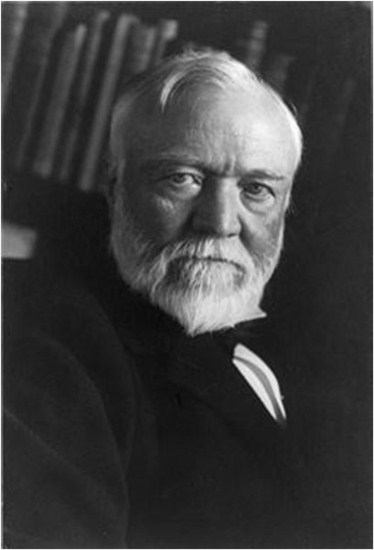

ANDREW CARNEGIE (1835-1919)

by Jeffrey Smith

Sponsored by Roche Constructors, Inc.

Perhaps no historical figure is better suited to discuss the relationship between libraries and democracy than Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie was an ardent believer in democratic government and principles; with a true rags-to-riches immigrant story, Carnegie was convinced that he could have risen from humble beginnings to become (as J. P. Morgan put it) “the richest man in the world” in a democracy unbridled by dominance by those of a privileged position based on inherited wealth. Free public libraries were a centerpiece of his thinking; he often referred to them as “temples of democracy,” feeling that they were the most democratic of all institutions since they only help those who help themselves.

Born in Scotland in 1835, Carnegie and his family emigrated to the United States in 1848 to live with relatives near Pittsburgh. Young Andy’s experiences were not unlike those of many immigrants who arrived with little, working in assorted factory jobs before joining a telegraph company where he learned telegraphy. This new skill gained him a position with the Pennsylvania Railroad as a secretary and telegrapher, where he worked his way up the ranks until “retiring” at age 30 to focus his energies on bridge-building, which led to steel manufacturing. Carnegie Steel became the largest manufacturer of steel rails on earth. It was here, in Pittsburgh, that Carnegie had access to the personal library of Col. James Anderson, who opened it as a lending library for “working boys” in the area. Later in life, Carnegie became convinced that Anderson’s generosity gave him a love of books and reading that were central to both his business success and personal happiness.

As a philanthropist, Carnegie focused much of his early effort on free public libraries. Since he had gained such wealth from the rapid industrial growth of the United States in the Gilded Age, he felt it was his duty to help expand opportunities for others to rise as well. Thus, he developed his idea of “scientific philanthropy,” which has a strong familiarity today. He would seek to expand democracy and peace through his giving, leaving other causes to fellow philanthropists (referring requests for medical funding, for example, to John Rockefeller, saying, “He’ll pay for it”). This general philosophy was first published in his 1889 article, “Wealth,” later given its more popular title, “The Gospel of Wealth.”

For Andrew Carnegie, the rich should strive to give away all their riches to advance the general society. As his other writings suggest, Carnegie felt that only in a democracy (unlike his native Great Britain) could one rise as far as his abilities and aspirations would carry him, unencumbered by a privileged class. For Carnegie, free public libraries – of which he funded some 1,700 in the United States alone – were among the greatest expressions and protectors of democracy.

RECOMMENDED READING

Carnegie, Andrew. The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986.

Carnegie wrote this memoir late in his life, encouraged to do so by his wife so that their friends and their young daughter Margaret would have his experiences in print. In many ways, it is a typical 19th century autobiography – Carnegie tells every story with a clear object, a sort of story-and-moral structure.

Morris, Charles R. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: Times Books, 2006.

An interesting approach to linking events over time, suggesting that these Gilded Age “robber barons” are the architects for the modern American economy, dominated by large corporations.

Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Penguin Press, 2005.

The most recent treatment of Carnegie by the renowned biographer, with a more approachable style and manageable length than others.

Wall, Joseph. Andrew Carnegie. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. 1970.

More than 1,100 pages long, this remains the standard biography. It is thoughtful, thorough, and beautifully written.

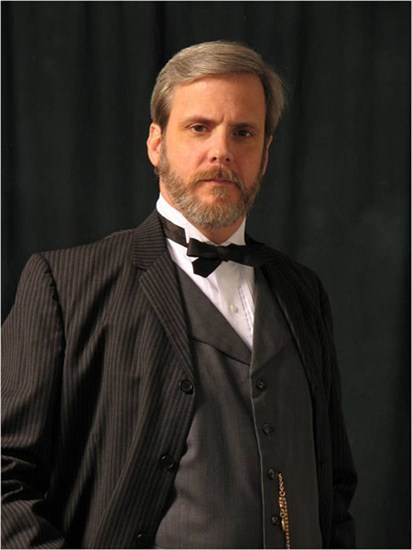

JEFFREY SMITH

Jeffrey Smith is the Chair of the History and Geography Department at Lindenwood University in St. Louis. He has portrayed Andrew Carnegie for more than 15 years and William Clark since 2003 in various Chautauqua festivals, including the Great Plains Chautauqua, Missouri Chautauqua, and the Greenville Chautauqua. Currently, Smith is writing a social history of Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

ANDREW CARNEGIE

· By funding the construction of more than 1,700 free public libraries in the United States and requiring tax support for operations, Andrew Carnegie fundamentally changed our views about libraries in our communities, large and small.

· In many ways, Andrew Carnegie is the architect of modern philanthropy – not only thinking in terms of the impact of giving on the broader society, but also on the obligation of the rich to enhance society. He is the philanthropic ancestor of Warren Buffett and Bill Gates.

· Carnegie believed that war had become an obsolete and inefficient way for countries to settle their differences. His writings on world peace sound as much like an editorial in today’s newspapers as they do an historical document.

QUOTES

“The best means of benefiting the community is to place within its reach the ladders upon which the aspiring can rise – parks and means of recreation, by which men are helped in body and mind; works of art, certain to give pleasure and improve the public taste; and public institutions of various kinds, which will improve the general condition of the people – In this manner returning their surplus wealth to the mass of their fellows in the forms best calculated to do them lasting good.”

Andrew Carnegie, Wealth, 1889

“The problem of our age is the proper administration of wealth, so that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship.”

Andrew Carnegie, Wealth, 1889

“I believe that higher wages to men who respect their employers and are happy and contented are a good investment, yielding, indeed, big dividends.”

Andrew Carnegie, Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie, 1920

“Put all your eggs in one basket, then watch that basket!”

Andrew Carnegie

TIMELINE

1835 Andrew Carnegie born in Dunfermline, Scotland.

1848 The Carnegie family moves to Allegheny, Pennsylvania; young Andy takes a job at a textile mill.

1853 By now a skilled telegrapher, Carnegie is hired by Thomas Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad as his personal telegrapher and secretary.

1855 Carnegie’s father, Will, dies.

1856 Carnegie makes his first investment in sleeping cars, buying stock in the Woodruff Sleeping Car Company; a year later, his investment returns more than three times his salary.

1861 Carnegie and Scott assist the Union Army in repairing telegraph lines at the start of the Civil War.

1864 Carnegie pays $850 to a replacement for him in the Union Army after being drafted. Construction begins on the Illinois & St. Louis Bridge across the Mississippi with Carnegie’s Keystone Bridge Company as construction company. The bridge was completed in 1874.

1872 Carnegie expands his steel manufacturing by fully embracing the Bessemer process. He opens the Edgar Thomson Works using the Bessemer process three years later.

1887 After the death of his mother, Margaret, in late 1886, Carnegie marries Louise Whitfield.

1889 Wealth published in England; it was republished as The Gospel of Wealth later that year in the United States.

1892 Strike at the Homestead Works; it ranks as one of the bloodiest and most notorious strikes in American labor history.

1897 Birth of Margaret Carnegie, the Carnegies’ only child.

1898 Carnegie works to achieve independence for the Philippines after the United States acquired the colony from Spain after the Spanish-American War.

1901 Carnegie sells his steel company to J. P. Morgan to create United States Steel. Morgan congratulates Carnegie on becoming “the richest man in the world,” and probably the world’s first billionaire.

1901-10 Carnegie becomes a vocal and active proponent of world peace and ending colonialism, founding several organizations to promote the end of war.

1903 Carnegie makes his first gift of $600,000 to Tuskegee Institute.

1911 Carnegie Corporation of New York is created.

1913 The Peace Palace at The Hague, funded by Carnegie, is dedicated – just a year before the start of the Great War.

1919 Carnegie dies at Lenox, Massachusetts.