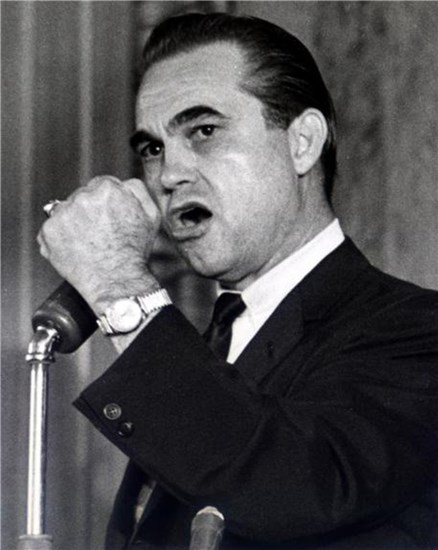

George Wallace (1919-1998)

by Doug Mishler

The 1960s was arguably the most dynamic decade in American history for it seemed everything was in flux. From 1954 to 1972 America’s cultural patterns altered dramatically. Concurrent with those changes came powerful demands for alterations in the treatment of women, blacks, and other minorities. These radical social-cultural changes also produced a profound reaction. Conflict arose between agents of change and those protecting the status quo and America erupted in assassination and violence. In many ways the horrors of the Vietnam War seemed just an extension of what was happening on America’s streets. From free love to protest to assassination and street riots, America in the 1960s seemed to be falling apart.

This toxic mix launched a semi-obscure Alabama governor into the national spotlight. George C. Wallace II became the symbol of the reaction to America’s social cultural changes. Wallace fought against change as a populist confronting a radical agenda that imperiled the lives of average Americans. Wallace led a movement to protect the “little man” from the destructive horde of what he called the “liberal elite.” Because of his resistance to change, many Americans saw Wallace as a villain. To others he was a hero.

Born in 1919 to a poor family in rural Alabama, George was always a fighter. He boxed throughout high school and college and later in his career got into a fist-fight with a state trooper. He made his way into the law school at the University of Alabama and worked dozens of jobs to graduate in 1942. He tried to get into the Air Force but they did not care for his too fast-pulse and skinny frame. He persevered and flew 11 missions over Japan for the Army Air Corps as a flight engineer on a B-29, even though he developed a fear of flying that lasted the rest of his life. He returned to Alabama to fight it out in politics, serving in the state legislature from 1946 to 1952 and then as an elected Circuit Judge from 1952-1958.

In 1958 Wallace made his first run for Governor as the reformer he had been on the bench and in the legislature. While Wallace emphasized states’ rights and the right of each citizen to control his social and cultural institutions, he was also known as a moderate who was color blind and more interested in improving conditions for all “the little people; the hairdresser, the barber, the mechanic,” than in maintaining the Southern racial system. His bid failed in large measure due to Southern reaction to the Brown vs. Board of Education court case and school desegregation. His opponent played the race card intensely and, with the aid of the Ku Klux Klan, beat Wallace. George learned a lesson and while he never gave up his populist stances he was also adamantly pro-segregation from that moment on.

While Wallace is often described as the “anti-man” for his resistance to nearly every new change on the national scene, he was a very activist governor. He won the Alabama governorship in 1962, 1970, 1974, & 1982 (his wife Lurleen served as governor of record while he ran the state from 1966-1968.) He served 16 plus years and built thousands of miles of roads, improved the education system with a school building and funding program (pay raises, books for students, new facilities), opened the first new Alabama university since the early 1800s, and brought in tens of thousands of new jobs to the state by enticing large corporations to leave the rust belt. He also dramatically increased social funding for “the little people,” bettering the lives of the elderly and poor. He was by all accounts a good governor with few scandals and a very modern social program that radically altered Alabama from the sleepy rural society it had been in the 1950s.

Despite his progressive impulses, Wallace is most famous for his first inaugural speech’s hyperbolic pledge of “segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Wallace launched himself into history and the national consciousness as a reactionary “standing in the school house door” against “those liberal pseudo-intellectuals” (like the Kennedys) who desired to “impose upon us doctrines foreign to our way of life and disrupt our tranquility.” He railed against the “liberal commie conspiracy to destroy individual rights” spearheaded by the judiciary and Civil Rights activists who “would tell us how to run our schools, who we can associate with, even how a schoolboy must wear his hair.”

Striking a nerve, Wallace quickly became a national force and ran for President as an independent in 1968 and a Democrat in 1972. “Standing up for America” in 1968 he won five states by espousing values that would soon be adopted by Richard Nixon and then Ronald Reagan. He desired to shrink federal power and increase the states’ power, he opposed activist judges, supported amendments to re-allow school prayer, and fought busing. Along the way he attacked the “pseudo-intellectuals who rode bicycles,” disparaged “hippies who need a bath,” and those traitor “peace protestors who worked for the commies in Vietnam.” While Wallace was the first politician to calculate that running against Washington was the way to win, he was a genuine populist ardently supporting the “little people” and the struggling middle class against the elite and rich. He was also the first to demand “law and order” and set the blueprint for other ‘70s and ‘80s politicians.

Wallace is most remembered for his support of segregation, his stand in the school house door, his apparent ordering of the beatings in Selma and Birmingham, and his seeming encouragement of violence against Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights “agitators.” To some this made him a great defender. To others this made Wallace a dangerous reactionary. Both these opinions are simplistic.

Wallace was ingrained with a deep hostility to Northern meddling in Southern racial matters. He saw the North as infested with racism as the south was and thus hypocritical when attacking the South. Devoted to Southern populism and state’s rights, he opposed court-ordered desegregation, busing, the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling and the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts as violations of Constitutionally-guaranteed state rights. As he noted, “If people in Maryland want to end segregation, they have every right to do so, but let them do it and not some bureaucrat or judge in Washington. If Alabama believes in segregation that is their business. Each state and people have the right to choose for themselves.” Wallace sincerely believed that government closer to the people would better regulate social decisions that protect everyone’s individual rights.

For many Americans though, “states’ rights” was code for Wallace’s racism, a charge that was further intensified by Wallace’s rhetoric. He couched his attacks against federal oppression with such nuggets as “I will fight for segregation...I will fight our enemies face to face and toe to toe and never surrender...right will prevail if we fight.” Many concluded that Wallace was a devout racist who believed in Ku Klux Klan-style violent resistance. His unceasing attacks on Martin Luther King, Jr. and other “commie agitators” his acid filled digs at “hypocritical northern limousine liberals” who should “do the country some good by jumping in the Potomac” and his belief that blacks were not equal to whites all reinforced the impression that Wallace was a die-hard racist.

Of course, that impression was only partially accurate. Though his rhetoric was fiery, in fact Wallace always referred to the Ku Klux Klan as “those people” and asserted that confronting segregation must be carried out only through legal means. While he was clearly paternalistic towards blacks as needing white assistance to develop their limited capabilities, he did not condone an outright denial of their legal rights. He allowed that blacks should assert their rights like everyone else, but that by doing so in the streets was anarchy and only intensified violence.

Wallace felt that segregation was slowly ending but that it was up to each state to choose the pace and course to end it. Privately Wallace had no problem with blacks and whites sharing facilities if that is what they wished to do. Known to be fair to both races, one black lawyer said, “Only Judge Wallace called me Mister.” Yet he felt that the pace of civil rights was too rapid and thus too unsettling for whites ingrained with a racial system of over two hundred years duration—rapid change did not foster justice but injustice, hatred, and reaction. As he noted about the Kennedys and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, “they can’t come in here and overnight tell us who we are going to work with, live with, eat with. It will only intensify the Ku Klux Klan, and that is why we get bombings and murders, the people feel helpless.”

Sadly, Wallace’s devotion to getting elected frequently compelled him to play the race card with rhetoric that inflamed society. He never saw till his later years that his combative rhetoric worsened the situation. After he was shot in 1972, he did not abandon his old platform, but he softened it. He realized that both he and the South had changed and in his final years he relied more and more on black Alabamians. He appointed more blacks to political office than all previous governors, including those during Reconstruction. By the 1980s the old and invalid Wallace looked inside his soul and realized that his fight against change in the 1960s was not really that different from the Ku Klux Klan in its effect. Famously he dropped into a black Birmingham church and begged, “I know now that I contributed to your pain and I can only ask your forgiveness.” He even met and prayed with Jesse Jackson and noted how the Rainbow Coalition and Stand up for America both were based on helping the average “little man.”

George C. Wallace would slowly leave the scene, but his life and his colorful political career changed America.

Recommended Reading

Palmer, Mary. George Wallace: An Enigma: The Complex Life of Alabama's Most Divisive and Controversial Governor: Intellect Publishing, 2016.

Carter, Dan. The Politics of Rage, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

Lesher, Stephan. George Wallace: American Populist, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing, Reading, 1994.

Doug Mishler

For over 20 years Doug Mishler has presented figures from Nikita Khrushchev to Theodore Roosevelt, to Ernie Pyle, and P. T. Barnum. He has made over 800 first person presentations of over 20 historical figures, including Stonewall Jackson, Henry Ford, and now Isaac Parker. He also has his own theatre company “RAT,” and teaches history at the University of Nevada. Like his idol T. R., Doug believes there is still plenty of time to grow up and get a “real job”—but later!

Bullet Points

-

The man who stood in the “school house door”

-

The main enemy of the Kennedy Administration

-

Shot down while he campaigned for President

-

The creator of Modern Populism—but he was a Democrat!

-

He promised to run over any hippies he found in the street

-

The most radical politician of his day

Quotes

"If any long-haired anarchist lies down in front of my automobile, well, it’s gonna be the last one he lays in front of."

"Free enterprise has solved more poverty than all the government projects combined."

"Middle America is caught in a tax squeeze between those who throw bombs in the streets while refusing to work, and the silk-stocking crowd with their tax-free foundations."

"I have an alternative to this illegal document, this Civil Rights Act. It is called the Constitution. It guarantees civil rights to all the people without violating the rights of anyone."

"There is not a dime’s worth of difference between the republican or democratic parties."

"I believe in segregation not for discrimination but rather as best for both races as they learn at their own rate."

"I detest those limousine liberal pseudo-intellectuals in Washington D. C. and Boston who don’t know how to park their bicycles straight."

"We fight in Vietnam with our hands tied behind our backs and our boys die for nothing."

"I never really hated anyone, yet after my shooting I realize more than ever the futility of hate."

"Watergate was a symptom of naked power unchecked by moral restraint."

"Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever, right will prevail."

Timeline

1919 Born in Clio, Barbour County, Southeast Alabama

1942 Paid his way through college as lightweight boxer and odd jobs, graduated University of Alabama Law School.

1943 After several attempts to enlist, joined the Army Air Corps.

1945 Appointed as the Assistant Attorney General of Alabama

1946 Elected to the Alabama House of Representatives

1952 Elected as an Alabama Circuit Judge, known as a liberal friend to African-Americans

1958 Lost primary for Governor due to Ku Klux Klan support for his opponent

1962 Wins a landslide for Governor of Alabama after a segregationist campaign

1963 Inaugural speech, ‘Segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever.’

1963 ‘Stood in the Schoolhouse Door’ at University of Alabama, blocking Black students’ entry

1963 Entered Democratic Presidential primaries, loathing John F. Kennedy and Civil Rights.

1966 Due to term limits in Alabama constitution, his wife Lurleen ran in his “place” and won as Governor. He ran the state until she died of cancer after 13 months

1968 Ran for President as the American Independent Party candidate and won almost ten million popular votes and swept votes across five Southern states

1971 Elected second term as Governor

1972 Ran for President as a Democrat moderate on race. He won primaries in Michigan and Maryland, but was shot May 15th in Laurel Maryland and left paralyzed

1974 Easily won third term as Governor of Alabama

1975 Lost Democratic Presidential primary to Jimmy Carter

1978 Openly renounced his racial approach and apologized to blacks for his past actions

1982 Won fourth term Governor of Alabama. Appointed record number of African Americans to his cabinet and other important state positions

1986 Retires after 16 years in office

1998 Dies after long illness