WILLIAM CLARK (1770-1838)

by Jeffrey Smith

Sponsored by High Sierra Water Services, LLC

For most people, William Clark’s first name is “Lewis and.” The 29 months he and Meriwether Lewis spent on their odyssey to the Pacific and back made them national celebrities, not unlike astronauts in the 1960s; William Clark and Meriwether Lewis were, in a way, the John Glenn and Neil Armstrong of their day.

They were perhaps the most famous explorers since Columbus, heading westward from their homes with many of the same motives. Thomas Jefferson wanted them to find “the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.”

The trek to the West beyond the boundaries of known terrain transformed Clark in ways neither he nor any of the others could have imagined. He returned as a man with a new respect for Native American peoples, which helped shape his vision of western development. He became one of the great boosters for the West and ranked among the most respected authorities on United States-American Indian relations – by both sides.

To William Clark, the West was a source of commercial activity and national prosperity, where government took an active role in protecting and facilitating expansion of trade, transportation, and culture. It was a place where Native Americans could evolve into “civilized” (i.e., agricultural, westernized) peoples under the protective eye of the United States. It was a source of scientific knowledge, commerce, and even a route to the lucrative Asian trade. And he planned to be part of it.

Part of his reward was an appointment as chief Indian agent for the region, which necessitated moving to the frontier town of St. Louis. He spent the rest of his life there, seeing the former French and Spanish settlement grow into a thriving western city and staging point for western development. He became quite the booster for the area, too, telling his brother that it “presents flattering advantages at this time and I think it will increase as the population increases, which is beginning to be considerable.” He became a leading voice in the great national debate about the West: How should it develop? What role should government play? What about all the people who already lived there when the United States acquired it?

Clark’s views on Native Americans didn’t endear him to many expansionists, either. He saw different races as part of a large body of humanity that can presumably rise to the level of “civilization” of the Euro-Americans with help through trade, training, schools, land, and even annuities. And he told them so. Clark’s home became the site of numerous negotiations between tribal leaders and himself. He often offered the same message he had in 1805, a paternalistic view that the “Great White Father” wished to help.

Today, we still leave William Clark stuck on the Corps of Discovery. After all, it did shape the rest of his life, leading him to a life connecting East and West, European and Native cultures with commercial realms. His gravestone in St. Louis’ Bellefountaine Cemetery, constructed as part of the journey’s centennial celebration, sports the heads of buffalo and bear. But it recognizes him as “statesman.”

RECOMMENDED READING

Foley, William E. Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004.

This is the definitive biography by Missouri’s most preeminent historian of the territorial and early statehood periods in Missouri history – and very readable as well.

Gilman, Carolyn. Lewis and Clark: Across the Divide. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2003.

The catalogue accompanying the traveling Smithsonian exhibition. Lavishly illustrated with excellent captions, beautifully designed, and spritely written. A good introduction to and overview of the Corps of Northwest Discovery and the period that launched it.

Holmberg, James, ed. Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Recently found letters from Clark to his oldest brother Jonathan, including one sent back from Fort Mandan in spring 1805 and another at journey’s end reporting on the successful return of the Corps of Discovery. These letters give a unique insight into Clark’s thinking on business interests, Clark’s feelings on the death of Meriwether Lewis, family affairs (including wife Julia’s dislike of the frontier town of St. Louis), and management of his slaves (including York).

Jones, Landon P. William Clark and the Shaping of the West. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

The other standard biography of Clark, written by a former editor of People. The history is absolutely sound with lively writing and a gift for storytelling. His chapter on Clark’s tenure in the Ohio Valley is stronger than Foley’s.

Moulton, Gary, ed. The Definitive Journals of Lewis and Clark. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Moulton devoted his life to this most recent edition. The one-volume condensed version of the multiple-volume set is also excellent. The annotations and explanatory footnotes are first-rate.

Ronda, James P. Lewis and Clark Among the Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

This is the definitive source on the expedition by one of the leading scholars on the West. Ronda takes exception with the idea that we don’t really know much about what the Indians thought about Lewis and Clark by demonstrating that a careful reading of the journals can tell a great deal about their thoughts and responses. Truly a ground-breaking work.

Smith, Jeffrey E., ed. Seeking a Newer World: The Fort Osage Journals of George C. Sibley, 1808-1811. St. Charles, Missouri: Lindenwood University Press, 2003.

This annotated journal of three years at the government-sponsored trade fort in Missouri under the supervision and command of William Clark gives a first-hand account of federal efforts to “civilize” the Native Americans through trade.

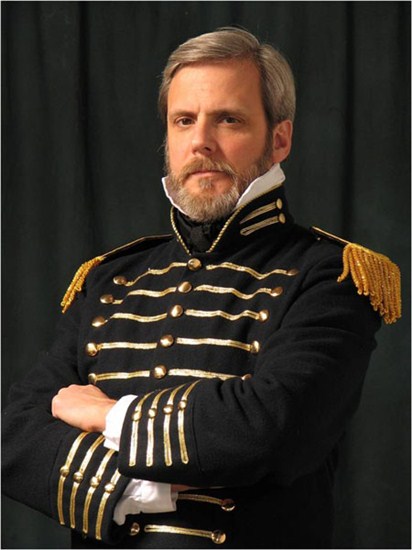

JEFFREY SMITH

Jeffrey Smith is the Chair of the History and Geography Department at Lindenwood University in St. Louis. He has portrayed Andrew Carnegie for more than 15 years and William Clark since 2003 in various Chautauqua festivals, including the Great Plains Chautauqua, Missouri Chautauqua, and the Greenville Chautauqua. Currently, Smith is writing a social history of Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

WILLIAM CLARK

· William Clark held many viewpoints about native peoples, thanks to his trek to the Pacific. He saw them as individuals and individual tribes with specific needs. Yet he also took the paternalistic view that they should be “civilized” with the help of the United States government.

· The eruption of what we now call “Black Hawk’s War” may have been Clark’s greatest diplomatic failure.

· Both paternalistic and friendly, caring and condescending, Clark’s record with Native Americans is perplexing at best. Yet he was among the most respected voices on American-Indian relations by both sides.

QUOTES

“This is an undertaking fraited [freighted] with many difficulties. But my friend I do assure you that no man lives with whom I would prefer to undertake such a trip as yourself.”

-William Clark to Meriwether Lewis, 18 July 1803

“To meet with the approbation of our country for the attempt which has been made to render services to the government by Capt. Lewis Myself and the party that accompanied us, is a source of the highest gratification. It will be a pleasing reflection in future life to find that the expedition has been productive of those advantages to our country, Geography, and science that you are willing to imagine.”

-William Clark to the Citizens of Fincastle, 8 January 1807

“When strong and hostile, it was our policy and duty to weaken them [the Indians]; now that they are weak and harmless and most of their lands fallen into our hands, justice and humanity require us to cherish and befriend them. To teach them to live in houses, to raise grain and stock, to plant orchards, to set up landmarks, to get the rudiments of common learning, such as reading, writing and ciphering, are the first steps toward improving their condition. But to take these steps with effect, it is necessary that a previous measure of great magnitude should be accomplished. That is, that the tribes now within the limits of the States and Territories should be removed to a country beyond those limits.”

-William Clark to Secretary of War James Barbour, 1 March 1826

“I did wish to do well by him [York] – but as he has got such a notion about freedom and his immense services, that I do not expect he will be of much service to me again; I do not think with him, that his services has been so great (or my situation would permit me to liberate him).”

-William Clark to Jonathan Clark, 10 December 1808

“I fear O! I fear the weight of his mind has overcome him.”

-William Clark to Jonathan Clark, on receiving news of the death of Meriwether Lewis, 28 October 1809

“Great joy in camp we are in view of the ocean, this great Pacific Ocean which we been so long anxious to see.”

-William Clark journal at Columbia River estuary, 7 November 1805

TIMELINE

1770 William Clark born in Virginia, the ninth of 10 children.

1783 The Clark family moves to Kentucky, including young William.

1794 While serving in the United States Army, Clark serves under Anthony Wayne at the time of the Treaty of Greenville.

1803 Clark accepts an offer from Meriwether to share the command of an expedition to the Pacific.

1804 May: Lewis and Clark leave Camp Dubois near St. Louis to travel up the Missouri River.

1806 September: the Corps of Discovery returns to St. Louis.

1807 While Lewis is attending gala celebrations of the return of the Corps, Clark is in Fincastle, Virginia, courting Julia Hancock.

1807 Clark appointed Indian Agent for the territory; Lewis became Territorial Governor.

1808 Marries Julia (called Judith by family and friends) Hancock.

1809 The Clarks’ first born child is a son, named Meriwether Lewis Clark.

1809 September: Meriwether Lewis dies en route to Washington; although Clark later accepted the story that Lewis had been murdered, he wrote his brother Jonathan at the time that “I fear his mind has overcome him.”

1813 Clark named governor of the new Missouri Territory, a post he held until Missouri statehood.

1815 Clark meets at Portage des Sioux with representatives of western tribes formerly allied with Great Britain and imposes treaties on them.

1820 Alexander McNair becomes Missouri’s first governor after soundly defeating Clark.

1824 Clark defeated in reluctant bid for a Senate seat.

1826 Clark meets the Marquis de Lafayette on the American tour of the former Revolutionary War protégé of George Washington.

1828 Completes government report with Lewis Cass regarding management of Indian Affairs.

1838 Clark dies in St. Louis, Missouri and is buried at his nephew, John O’Fallon’s family cemetery.