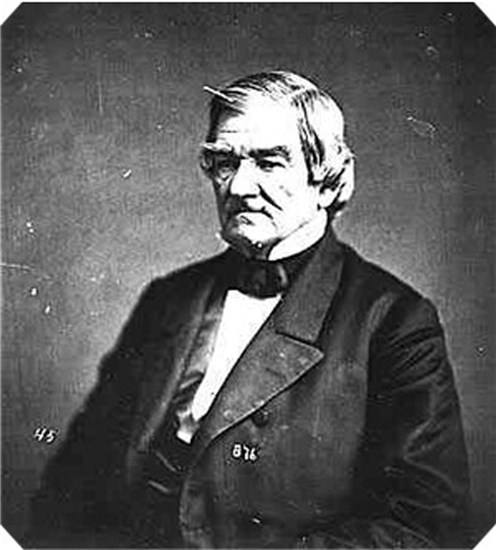

Chief John Ross (1790-1866)

by Michael Hughes

Sponsored by Myra Monfort-Runyan

For decades before the Civil War, the Cherokee people had been allied with the United States. The Cherokee tribe was the most unified and prosperous of all American Indian nations. By the war’s midpoint, the tribe was split in its loyalties, a third of its women were widows, and scarcely a building was left standing on its reservation. At the center of this tragedy was John Ross.

John Ross seemed destined to be a member of the white elite of the Confederacy. Seven of his eight great-grandparents were Scottish-American settlers of future Confederate states. Ross gained fame when he fought to defend white settlers against Alabama’s Creek Indians and when he founded the Tennessee commercial center later named Chattanooga. He gained wealth as owner of a Georgia slave plantation.

However, Ross still felt the pull of Cherokee ancestry. Over time he became a champion of the tribe’s traditionalists. Ross was elected chief just as the Southern states were attempting to seize the last Cherokee lands within their boundaries. State officials encouraged trespassing, theft, and violence against the Indians. In 1835, a tribal faction surrendered and signed an illegal treaty agreeing to remove the Cherokee west to Indian Territory. Ross accompanied the last party to leave the homeland. His first wife was among the 3,000 Cherokee who died before reaching present-day Oklahoma.

On arrival, Ross took part in the unification of several rival groups under one government. But the eventual Cherokee recovery was endangered as the Civil War loomed. The United States stopped the payment of treaty obligations and the protection of “civilized” Indians from Plains raiders. Confederate representatives attempted to lure Cherokee who identified with the white South and slaveholding into signing a treaty. The Cherokee tribe faced its own civil war. When pro-Confederates swayed a mass meeting, Ross gave in to an alliance in order to prevent tribal division.

Several months later a Ross-approved Cherokee regiment deserted when ordered to take part in killing non-Confederate Creek Indians and escaped slaves. Thousands more Cherokee began to escape increasing depredations by Confederate troops. Ross fled to meet with President Abraham Lincoln. Refugee legislators met to approve support of the Union and the abolition of slavery. Later, Confederate supporters would in turn flee violence from Union soldiers.

A majority of members of the Cherokee and several other Indian Territory tribes either retained or renewed loyalty to the United States. Despite this, the existence of Confederate treaties with Indian signatures played into the hands of U.S. commissioners at war’s end. They argued that the documents invalidated the tribes’ previous agreements, governments, and reservation boundaries. To divide the Cherokee tribe, they promised its former Confederates a separate reservation.

Ross exhausted the last months of his life fighting the changes. While dying, he at last received word that the Cherokee nation would be left intact. However, provisions in the new treaties of the Indian Territory would eventually threaten the existence of every Indian reservation across the West.

Recommended Reading

Confer, Clarissa W.The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War. University of Oklahoma Press, 2007.

Hughes, Michael. A.Journal of the Indian Wars: The Indian Wars’ Civil War. Savas-Beattie Publishing,2006 reprint.

McLoughlin,William G. After the Trail of Tears: The Cherokees’ Struggle for Sovereignty, 1839-1880. University of North Carolina Press,1993.

Moulton, Gary E. John Ross, Cherokee Chief. University of Georgia Press, 1978.

Warde, Mary Jane.When the Wolf Came: The Civil War and the Indian Territory. University of Arkansas Press, 2013.

Michael Hughes

Dr. Michael Hughes formerly taught Art History, United States History, and Native American Studies at East Central University in Oklahoma. Like his subject, John Ross, he is of Eastern Cherokee descent. The Chickasaw, Cherokee of Oklahoma, and Comanche nations were among early sponsors of his Ross performances. His other twelve characters include Alexander Graham Bell, Jim Bridger, Michelangelo, Ernie Pyle, and Orson Welles. Michael is the author of around 55 articles and books in his fields and he was an editor of Encyclopedia of Oklahoma and Journal of the Indian Wars. His wife, Eril Hughes, is a professor of English.

Chief John Ross

-

Was devastated by a civil war within the Civil War.

-

Was betrayed by the Confederacy and the Union alike.

-

Freed and enfranchised slaves ahead of the United States.

-

Was dispossessed by the United States his people fought and died for.

Quotes

“The Cherokee Moses”—Commissioner of Indian Affairs Thomas L. McKenney.

“We are in the situation of a man standing alone.”—Chief John Ross, 1861.

“[T]he horrors of civil war . . . are greatly to be deprecated . . .”—Chief John Ross, 1862.

“If he is a rebel, there is none loyal.”—A pro-Union Cherokee, 1866.

Timeline

1790 John Ross (Tsan Usdi or “Little John”) born at the Cherokee town of Turkey on the Coosa River in Alabama.

1814 Ross and 600-700 other Cherokee fight as allies of Andrew Jackson in the Creek War.

1819 Ross elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee.

1810-20s Ross establishes trading community of Ross’s Landing at present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee.

1835 Cherokee minority faction signs a tribal removal treaty in violation of Cherokee law.

1838-39 Cherokee “Trail of Tears” emigration west to Indian Territory; Ross’s wife Quatie dies en route.

1839 Reunification of the Cherokee nation and rewriting of the Cherokee constitution.

1861 Confederate agents arm Stand Watie and other pro-Confederate Cherokee and issues threats against the Cherokee

National Council.

1861 Ross yields to the signing of a treaty with the Confederacy in the interests in tribal unity.

1861-62 Over 7,000 Cherokee flee to Union lines to avoid having to fight neutral and pro-Union Indians and to escape

depredations by Confederate troops. Ross escapes to meet with President Lincoln.

1863 Cherokee traditionalists successfully urge the National Council to repudiate the Confederate alliance and emancipate

the Cherokee slaves.

1865 Commissioner of Indian Affairs Dennis Cooley cites Confederate treaties with the tribes as an excuse to end tribal

governments and annex Indian land.

1865 Ross goes to Washington, D.C. to try to prevent the dismemberment of his tribe.

1866 Ross dies on August 1 as President Andrew Johnson intervenes to permit the reunification of the Cherokee tribe.