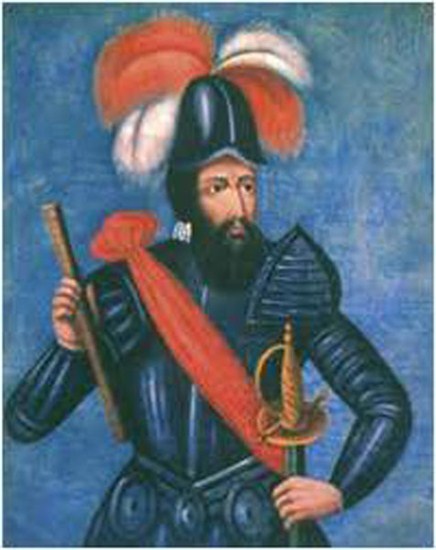

FRANCISCO PIZARRO (1475-1541)

By Hank Fincken

As a general, he was brilliant. Peace did not become him. Francisco Pizarro was born out of wedlock and denied all gentlemanly advantages. Yet he managed to conquer much of South America and destroy the Inca Empire. His bravery and commitment are undeniable; his ruthlessness and cruelty affect a continent today. For 400 years, his courage was celebrated in history books. Today he is remembered as one of the world’s great villains. But then again, maybe those in the 21st century are as naively single-minded in their search for virtue as the 16th century Spaniard was in his search for gold. This performance will not try to remake Pizarro into a hero, but it will try to put flesh and blood on someone who is remembered mostly for his shedding of flesh and blood.

The meeting and eventual battle between the Inca Atahualpa and the Spanish Conquistador in November 1532 in Cajamarca Peru is not just about the boundary between hero and villain. The time and the battle invite exploration of the boundaries between civilized and uncivilized, Christian and pagan, and the question of who decides the physical boundaries between nations.

Looking across the centuries, one can see that these boundaries are constantly in flux. It is only in the “now” that they seem solid and permanent. In 1535, to Europeans, Pizarro seemed a hero and Atahualpa the Devil’s partner. It was considered a religious mandate to change the physical boundaries of both nations in order to save souls. Today, people appreciate the achievement of the Incas and despise the greed of the Spaniards. Many prefer to believe the Inca Atahualpa was a great martyr and Pizarro the great exploiter.

Of course there is some truth in this interpretation. But, current boundaries between good and bad, hero and villain, civilized and uncivilized are as limiting and short-sighted as the old. These new boundaries encourage simplifying the past rather than trying to understand why the two cultures had such a violent encounter.

Society seems as trapped in this moment of time as Atahualpa and Pizarro were trapped in theirs. However, today’s observer has the advantage of realizing that each century’s interpretation of the conflict is based as much on wishful thinking and values of the moment as it is on events. Atahualpa was also a great exploiter of his neighbors; Pizarro’s final act in life was to draw a cross with his own blood on the floor.

The two men had more in common than either would care to believe. Atahualpa saw himself a deity; Pizarro a deity’s representative. Both men used good manners to disguise ambition, believed it was their destiny to rule the world, and trusted military might as the means to this end. Boundaries enabled both to see the other as an enemy.

Boundaries define who and where one is. Yet they also limit appreciation of the other and what could be. The Spanish ideal of chivalry included hospitality. The Inca used a work tax to overcome national disasters and to sponsor lavish religious ceremonies. Despite what conventional boundaries implied, war was not inevitable. It remains a five hundred year history lesson that peace and compassion may be worth dying for, just not worth killing for.

RECOMMENDED READING

Bernhard, Brendon. Pizarro, Orellana, and the Exploration of the Amazon. Chelsea House Publishing, 1991.

Busto, Jose Antonio del. Francisco Pizarro: El Marquez Gobernador. Librerias Studium Editores, 1978.

In Spanish, this book has some of the best details I ever found about the Spanish culture in 1530.

Cieza de Leon, Pedro. The Discovery and Conquest of Peru. Duke University Press, 1998

(The original was published in 1550.) It’s the early Spanish view of the Conquest.

Guaman Poma de Ayala, Felipe. Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno. 1615. www.kb.dk/permalink/2006/poma/info/es/frontpage.htm

This manuscript was discovered in 1907. Its Inca-descendent author hoped that an accurate description of the Incas and the Conquest would change Spanish policies. It is the closest document to a primary source ever found. The drawings alone make it a great anthropological tool.

Hemming, John. The Conquest of the Incas. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1970.

This book is probably the first serious English study of the Conquest and is still a classic.

Jacobs, William Jay. Pizarro: Conqueror of Peru. First Book-Biographies, 1994.

This book is especially good for 5th and 6th grade.

Kendell, Ann. Everyday Life of the Incas. Dorset Press, 1989.

Mann, Charles C. 1491. Knopf, 2005.

The perfect example of how our values today help us redefine the past – again.

Prescott, William. History of the Conquest of Peru. Dover Publications, 2005. (Originally published in 1847.) There are two ways of reading this classic. You can be very impressed that a blind author living in the USA managed to learn so much about the Incas so long ago or be upset that he doesn’t have 2013 insights.

Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford University Press, 2004. This book focuses more on Mexico, but the insights also relate to Pizarro and Columbus. It provides a fresh view of an old subject.

Sullivan, William. The Secret of the Incas. Crown Publishers, 1996.

This book will give you insight into the Inca religion and how the Incas saw themselves connected to the stars.

Varon/Gabai. La Ilusion del Poder. Institute of Peruvian Studies, 1997.

In Spanish, this book studies how the Pizarro family continued its conquest after Francisco’s death.

HANK FINCKEN

For more than 25 years, Hank Fincken has toured the U.S. performing his eight original first-person portrayals for Chautauqua festivals and other public venues. His characters include Thomas Edison, Johnny Appleseed, Francisco Pizarro, Christopher Columbus, Henry Ford, W.C. Fields, and an 1849 Argonaut named J. G. Bruff. He was awarded the title “Master Artist” by the Indiana Arts Commission, “Outstanding Performer” by the Indiana Theatre Association, and has received three national “Pinnacle Awards” for his teaching of history through video conferencing.

Hank was recently in a Hollywood film which featured Thomas Edison, wrote an original play for the city of Defiance about a teen abducted by the Shawnee in 1793, and performed as Prosecutor Richard Crowley in Susan B. Anthony’s trial in Adams, Massachusetts (her birth city). In the summer of 2013, Hank will perform as Johnny Appleseed for Ohio Chautauqua and as Thomas Edison in Nevada. This is his second time to be part of the High Plains Chautauqua.

FRANCISCO PIZARRO

· Pizarro was born with no future and conquered a continent.

· Civil war and disease set the stage for Inca leader Atahualpa’s loss.

· It’s easy to see what Atahualpa should have done because we have the benefit of hindsight. It was not so obvious then.

· 168 Spaniards versus a seasoned army of at least 40,000 Incas. Hate the Spaniards if you want, but they had courage.

· When Atahualpa arrived with his entourage, many Spaniards were terrified.

· When Atahualpa realized the Spaniards’ goal was gold, he promised to fill his cell, a room measuring 22’ x’17’ x 8,’ with it and another similar room with silver twice for his freedom. He did and offered to do it again before they executed him.

· The gold stimulated an inflation that made the poor poorer. In Spain, much of it was used to finance war.

· Many historians believe King Fernando, King Carlos I’s grandfather, was Machiavelli’s model for The Prince.

· Every civilization tends to view its barbaric acts as less barbaric than its neighbor’s barbaric acts.

QUOTES

Francisco Pizarro was illiterate; therefore, he wrote nothing down. The few quotations we do have were written by acquaintances many years later. That means that each is a bit suspect when it comes to accuracy. The quotations may reflect the acquaintance’s goals more than Pizarro’s.

“Choose. You may return to the poverty of Panama or cross this line and come with me through infinite dangers but eventual wealth.” – On the island of Gallo, Pizarro was ordered to abandon his quest by the Governor and return to Panama. Pizarro challenged his men to disobey this order, cross a line in the sand, and remain on the island. Thirteen men stayed and all were eventually given the title “Hidalgo” (Gentleman).

“Prepare your hearts as a fortress, for there will be no other.” – Pizarro’s final words to his men before the Battle of Cajamarca.

“Why do you take so long about dying?” – attributed to the assassin De Rada during his fight with Pizarro’s in Lima, Peru. A group of 20 attacked the Viceroy’s palace on Sunday, June 26, 1541.

“Make your confession in hell!” – again attributed to De Rada just before cutting off Pizarro’s head. Pizarro had drawn a cross on the floor with his own blood and asked for last rites.

“Every horse thinks his owner is the fattest.” – old Spanish saying

“Use this city as your home.” – message from Atahualpa to Pizarro when the Conquistador first arrived in the vacated Cajamarca.

“We have been displeased by the death of Atahualpa since he too was a monarch.” – King Carlos I of Spain when learning of Atahualpa’s execution.

“The conquest of Peru began with a checkmate.” – historian John Hemming, referring to the Battle of Cajamarca, in which Pizarro captured Atahualpa alive.

TIMELINE

1470 Incan leader Topa Yupanqui defeats the Chimu, uniting the coast and the Andes of what is Peru today. By 1530, the Inca empire stretches 3,400 miles north to south.

1474 Pizarro is born – maybe. Scholars debate dates from 1470-1478. Legend says he herded pigs as a boy.

1502 Uneducated Pizarro comes with Columbus’ replacement, Nicolas de Ovando, to Espanola to live with an uncle or in 1509 with Alonzo de Hojeda. Historians disagree.

1513 Pizarro has become an officer and works under Vasco Balboa when the group becomes the first Europeans to see the Pacific Ocean.

1519 Pizarro befriends the Governor of Panama, leads an expedition that arrests the popular Balboa and assists with his execution. Pizarro’s reward is to be made Mayor of Panama City for four years.

1519 Pizarro’s second cousin, Hernando Cortez, conquers the Aztecs.

1522 Pascual de Andagoya leads the first expedition along the western coast of South America looking for “El Dorado,” sometimes described as a man and other times a place rich in gold. He fails.

1524 Pizarro forms a company with two other Spaniards, Father Hernando de Luque and Diego de Almagro, and sails south looking for a gold city called Biru. They fail.

1526 Pizarro and Almagro try again, this time going much further south to the area known today as Tumbes. They find evidence of much gold, but the new gobernador of Panama denies Pizarro’s request to lead a third voyage.

1529 In Spain, King Carlos I grants Pizarro the titles of Governor and Captain General as part of the “la Capitulacion de Toledo.” Almagro and Luque receive lesser titles.

1530 Pizarro and Almagro leave Panama on a third expedition in December.

1532 With 168 Spaniards and countless Indian auxiliaries, Pizarro captures the Inca, Atahualpa, in Cajamarca on November 16. To gain his freedom, Atahualpa pays the largest ransom in history: 13,420 pounds of gold and 25,000 pounds of silver.

1533 Pizarro executes Atahualpa in July, crowns a new Inca, and marches 600 miles toward Cuzco. On the way, the new Inca mysteriously dies.

1533 In Cuzco in November, Pizarro crowns another son of Huayna Capac (Atahualpa’s father, too) Manco Inca. In many ways, Cuzco proves to be a gold city.

1535 Pizarro founds Lima, Ciudad de los Reyes. Carlos I of Spain divides Peru into two large land masses: Nueva Castilla and Toledo. Almagro leads an expedition into Toledo in search of another gold city. He fails. His group is called The Men of Chile.

1535 Manco Inca leads a revolt against the Spaniards in the fall, putting Cuzco under siege for 15 months.

1537 Embittered Almagro returns to Cuzco and declares himself Mayor. Civil war ensues. Manco befriends Almagro.

1538 At the Battle of Salinas in April, Pizarro defeats his ex-partner, Almagro, and executes him. Manco retreats to the jungle and establishes a new, smaller empire.

1540 King Carlos learns of Almagro’s execution, blames Pizarro, and creates new rules for Spanish settlers and the treatment of Indians. These rules foment rebellion.

1541 Pizarro is murdered by his partner’s son, Diego Almagro, and other survivors of The Men of Chile on June 26. The blood letting has just begun.